I am going to share 2 observations that will seem contradictory to each other - and that’s the point.

Observation #1

The belief in smaller, leaner teams being superior has captured the zeitgeist of the tech industry in recent years. The idea that teams can move faster, act with more agility and build more cohesion when they are small in sized is certainly not new (re: Amazon’s two-pizza teams). But in the last 1-2 years, it has caught on like wildfire. Personally, I attribute this to some recent secular trends -

Tech companies are operating with tighter fiscal constraints in what has been a 'risk-off' macro environment1 This has led many organizations needing or wanting to accomplish bigger goals with smaller teams, after a prolonged period of ubiquitous, mass layoffs (re: Meta’s Year of Efficiency).

Many larger, established organizations have struggled to innovate or keep up rapidly with industry trends in comparison to smaller, leaner startups. This has always been true to a degree - speed is a competitive advantage for startups - but has felt more pronounced in post-COVID market conditions. The few who have managed to innovate better tend to benefit from having invested in small, lean innovation/incubation/skunkworks squads (re: Figma Slides).

The advent of AI productivity tools is showing the potential for massive efficiencies in how we approach knowledge work, and promise a dramatic reduction in the busywork of collaboration and coordination that we incur particularly. These innovations have signaled a seemingly inevitable future where knowledge work is dramatically more efficient, though also raising the threat of widespread worker displacement too.

Observation #2

In my experience, I’ve rarely seen team leaders advocate a reduction in their team staffing specifically as a way to accomplish more or move faster. Team leaders & PMs pitching for more headcount for their areas is an event as frequent as trips to the grocery story. But the act of proactively advocating for a reduction in their team’s headcount, in contrast, is a once-in-a-blue-moon event.

Let me create a distinction here. We reduce or reallocate headcount from one team to a different area all the time, as a factor of prioritization decisions. What is far less common is when such a reduction originates from a bottoms-up belief, from the leaders of the team, that it will be a catalyst for better or faster execution. That is what is rare. In spirit - though perhaps only shared in quieter forums - these same leaders might even agree that their teams would benefit from being leaner. But in practice, there are a number of explicit & incentives and constraints at play that hold them back from acting on that intent.

Today’s essay does not dig into why this behavior is prevalent, thought that would be interesting to unpack too. Rather, today’s essay is about highlighting that the coexistence of #1 and #2 above is a meta-level misalignment that is so costly for so many organizations and leaders. And my belief is that us, as product leaders specifically, need to adopt a new mental model to address it: what I like to call, playing the headcount accordion. The premise is this: just as an accordion creates music through both expanding and contracting their instrument, modern product leaders know exactly when to expand teams and when to contract them to maximize impact.

Let’s explore this together.

The who, how and when of resource planning

Traditional resource planning & headcount allocation processes are designed around 3 main dimensions -

Who drives the decision making?

Are headcount decisions initiated and made top-down (executive team, senior leadership) vs. bottoms-up (led by team leaders closest to the work) vs. some form of collaborative back-and-forth?

How connected are the decisions to current or new strategies?

To what degree is there a need or appetite for bigger changes to company or product strategy (based on macro changes in market conditions, competitive or technological landscape, impact from current strategies, etc.) - or largely a continuation of stable existing strategies and status quo operating models?2

When are strategy and resource planning decisions made?

Are resources primarily determined and allocated through one-time, large-scale, annual planning processes vs. distributed in an agile manner on an ongoing, rolling basis vs. tied to specific company events or fundraising milestones?

A common pattern in the past was that as tech companies matured from early-stage/growth-stage startups to more established, scaled organizations, their approaches to resource planning would generally shift (1) more top-down (2) more stable and (3) less frequent. This wasn’t a hard rule per se, but fairly generalized as a long-term industry trend.

But this pattern has been breaking down in recent years. We are increasingly seeing companies of all stripes craving more agility to respond to rapid changes in the industry and operating environment. And specifically, from my vantage point, more established companies need to act more like startups3. This broader trend is powerful, since ‘acting more like a startup’ can influence almost every aspect of their approach to strategy, planning, execution, culture and the ‘social contract’ between leadership and employees. And from my perspective, the specific avenue of strategy alignment and resource planning is where this all comes to a head.

Product leaders, as accordion players

Let’s revisit the key tension above. How may we reconcile the challenge of organizations craving the ability to act more like startups (be faster, more nimble and run leaner) with the on-the-ground reality that so many team leaders have a different mindset and contradictory incentives & constraints? This is not to say one worldview is necessarily right or wrong. But what I would assert is that us product leaders are best positioned to harmonize these seemingly contradictory worldviews. And we have a responsibility to do so too. But for many of us, this necessitates more than just awareness of the tension. It requires a more fundamental mindset shift.

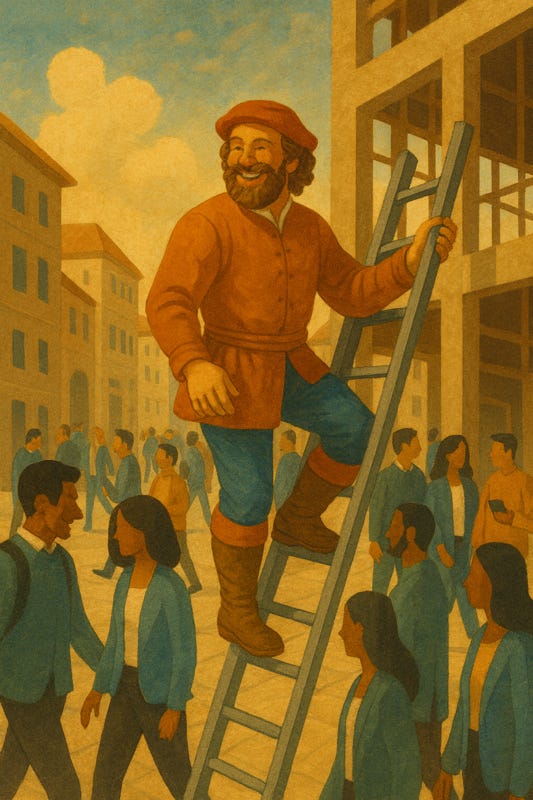

Today, many product leaders view headcount allocation as a ladder to navigate. In a ladder, you can only go one of two ways - you can either climb up or down. Similarly, they see resource allocation as an exercise to either increase headcount (if their scope is viewed as high priority) or see it decrease (if their scope is viewed as lower priority). While there may be some truth to this, this one-dimensional view can contribute to some challenges that only really show up at the global, organizational level -

Headcount footprint tends to grow monotonically over time. There is often a lower threshold and higher appetite to grow than to reduce. In fact, there is an active stigma around a reduction in headcount. And generally, headcount allocations tend to calcify around existing team structures.

Bigger changes and pivots in company strategy require major, disruptive changes to org design and resource allocation. These require a heavy amount of top-down ‘activation energy’ from leadership to execute well. But, ironically though not surprisingly, these changes almost always hurt velocity, once you factor in the high cost of change management.

In the new world we’re in, the better mental model for product leaders today is to approach resource planning as if they can play an accordion. When playing an accordion, both the acts of expanding and contracting its bellows, along with its keys, is what allows you to craft a wider range of melodies. The expansion gives way to contraction, and the contraction gives way to expansion. Similarly, when it comes to headcount allocation, we can approach it both ways. In other words, resource planning goes far beyond just growing or shrinking headcount. It is about knowing exactly when you need to expand and when you need to contract - and why. And embracing both acts as positive and impactful.

The only way to truly know when is the right time to expand or contract headcount is to be close enough to the product, to the team and to the ground to understand tradeoffs. And to then have good judgement - and trust of the leadership. To pick the perfect melody to play, so to speak. These decisions end up being a mix of science and art.

But in general, my advice to product leaders is to focus on 3 dimensions that typical, ladder-like thinking does not explicitly account for -

Momentum of execution

Whenever teams I lead advocate for more headcount, I tend to ask myself a few questions ex: do they have a strong problem space or motivating insight, and a credible path to realizing impact? do they have a strong group of core leaders that work well together? what is the opportunity cost of staffing this over X or Y? At some level, all of these questions are getting at the same core need: do we have momentum on something important4? And in the vast majority of cases, I’ve found that adding incremental staffing only helps when you already have strong momentum - irrespective of scope or scale. Even then, adding too much staffing can still be counterproductive to building or sustaining momentum as a team.5

Maturity of product

At the risk of over-generalizing, I would say that a fairly predictable pattern for products (or business drivers, or strategic bets, or platforms…) is that they operate best when teams are kept small at the ends of their maturity - their earliest phases and their latest phases (think: Explore or Extract in Kent Beck’s 3X framework). Those are phases of the journey where scarcity of resourcing is an asset, and abundance of resourcing is a liability. In contrast, products can benefit from heavier staffing during the ‘messy middle’ phase (Expand) - after the core hypothesis has proven out, but while most of the scaling, fleshing out, maturing and go-to-market is ahead of you. In those phases, both scope and headcount levels have been earned and de-risked. Too many teams apply too much staffing at the wrong phases, and too much runway to the middle phases6.

Model of the team

Admittedly, this is a bit newer - but for many product leaders, it can be worth evaluating whether your current product team model & composition allows you to leverage newer AI tools to their fullness. These tools promise to unlock newer, rapid ways of working (ex: XFN workflows designed around rapid prototyping & co-creation) - but also rely on significantly more crossover swarming over traditional functional lines. This introspection may lead you to consider new team models, ratios and operating models designed around (i) smaller teams (ii) more convergence across functions and (iii) newer flexible and adaptable talent profiles (aka “guilds of polymaths” from my previous essay).

In conclusion

For product teams, resource planning & headcount allocation is far more nuanced and complex than we give ourselves credit for when we apply traditional, ladder-like thinking. Playing the accordion allows us to approach resource planning with strategic acumen and agility. It encourages us to direct headcount to where it will actually make a difference, tightly align incentives at both global & local levels of the organization and embrace a more open-minded, learning-oriented way of setting our teams up for success.

The next step is for you to consider how you might apply this mindset, in your next planning exercise and in the ways you seek to influence your organization. Will you keep moving up or down your headcount ladder, or will you start playing a new tune?

Except for frontier AI companies! :)

The canonical evidence of a broader trend shift is the rising popularity of Zero-Based Budgeting (ZBB) or ZBB-lite planning models in the industry. For most tech companies, this disruptive resource planning model used to be reserved for adapting to recession-like economic conditions. But now, we are seeing it being applied more liberally, often as a forcing-function to drive strategy realignment and rigor.

I attribute much of the fervent discourse & debate of “Founder Mode” last year to this.

By focusing on momentum first, we choose to put scope second. For many teams, it is tempting to make headcount decisions based on scope of work. I would argue it is the most common shorthand we use fro resource planning in most tech organizations. In practice, scope is only predictable & estimable after you have early momentum. While momentum can be built from the ground up, scope can only be earned after-the-fact.

It can be helpful for organizational leaders to develop a clear opinion on the bounds of minimal viable staffing vs. maximum viable headcount for their teams, and assess that over time. At what point is the team too small to be viable, and at what point is the team too big to where incremental staffing would be net-negative? We sometimes only focus on the former.

I would nudge product orgs to establish a common vocabulary to align on what phase their bets are in. This can look different depending on the nature of the bet (ex: Explore <> Expand <> Extract for new products, or Early <> Intermediate <> Advanced <> Retired for platform capabilities), but there is a lot of value in aligning on ‘where are we?’ as a way to enable good decision-making.